Three days ago, Shohei Imamura was one the world's ten greatest living directors. That list will need revising, as Imamura has died at the age of 79. Imamura, whose credits include the masterpiece The Ballad of Narayama and an obscurity called Pigs and Battleships, was a true maverick. As far as I know, he's the first major post-humanist to emerge in Japan, getting his feet wet just before the other great rebel of Japanese cinema, Nagisa Oshima, went into feature filmmaking. While his peers busied themselves telling classical humanist tales with such lofty titles as The Human Condition and The Burmese Harp, Imamura picked at our festering scabs. His movies, adorned with such shlocky titles as The Insect Woman, explore not so much the human condition but the ways in which we resemble insects and pigs.

Three days ago, Shohei Imamura was one the world's ten greatest living directors. That list will need revising, as Imamura has died at the age of 79. Imamura, whose credits include the masterpiece The Ballad of Narayama and an obscurity called Pigs and Battleships, was a true maverick. As far as I know, he's the first major post-humanist to emerge in Japan, getting his feet wet just before the other great rebel of Japanese cinema, Nagisa Oshima, went into feature filmmaking. While his peers busied themselves telling classical humanist tales with such lofty titles as The Human Condition and The Burmese Harp, Imamura picked at our festering scabs. His movies, adorned with such shlocky titles as The Insect Woman, explore not so much the human condition but the ways in which we resemble insects and pigs.If you've never seen an Imamura movie, my description might be a little off-putting. In fact, his film sound a little like the formally accomplished but "moronic" films of a similarly zoologically-oriented auteur, the Cannes-feted Bruno Dumont, who makes some of the most repulsive films on the planet. The difference may be that Dumont's method consists of him imposing a set of reductionistic principles (humans consumed by animalistic instincts) pulled out of his ass onto a borrowed "Bressonian" framework. This is passed off as a kind of profound world-view or "vision".

However astringent his view of humanity, Imamura doesn't succumb to such reductionism. His wacky peasants and sundry lowlives may plow through life guided only their mouths and loins -- they're largely driven by instinct, thirst, hunger, avarice and sex -- but they still find room for a little fun. In totally commiting himself to a kind of anthropological realism, Imamura disavows the often mushy and sentimental humanism that dominated post-war Japanese cinema. But in retaining his sense of humor and giving his characters at least a chance to dream and hope, he avoids the ant-farm sophistry of would-be anthropologists like Dumont. I guess the difference is that in Shohei's films, sex can be enjoyable -- for the viewer and for the onscreen participants.

However astringent his view of humanity, Imamura doesn't succumb to such reductionism. His wacky peasants and sundry lowlives may plow through life guided only their mouths and loins -- they're largely driven by instinct, thirst, hunger, avarice and sex -- but they still find room for a little fun. In totally commiting himself to a kind of anthropological realism, Imamura disavows the often mushy and sentimental humanism that dominated post-war Japanese cinema. But in retaining his sense of humor and giving his characters at least a chance to dream and hope, he avoids the ant-farm sophistry of would-be anthropologists like Dumont. I guess the difference is that in Shohei's films, sex can be enjoyable -- for the viewer and for the onscreen participants.It must be said that the old sensei's hands were not entirely steady -- he's not a smooth filmmaker or a graceful storyteller. Much like the world he depicts, Imamura's are messy, unruly, a little unfinished. One moment you'll gawk at a series of stunningly artful compositions (in Pigs, a lengthy sequence of Japanse girls getting raped by American soldiers is composed in abstracted squares within diamonds like a kaleidoscope) that rival Ichikawa or Seijun Suzuki, but the next moment the film will abruptly veer into deliberately artless realism. Sometimes, as in The Pornographers, Imamura's herky-jerky rhythms and taste for unmotivated tonal shifts undermine the material. At his best, though, the oscillating tones and seemingly incongruous visual motifs come together to achieve a kind of grace. In Black Rain, Imamura's deeply moving portrait of post-atomic Hiroshima, the young protagonist's failure to find a suitable mate becomes something of a morbid joke, even as the tragic signs of her radioactive exposure are shown to be ever more pronounced. And one of the most memorable shots in cinema comes at the end of Dr. Akagi, when the doctor's assistant and obsessive whale-hunter finally chases down the giant mammal just as a giant "liver-shaped" mushroom cloud forms behind them. Only a true wacko is capable of creating such unique images. And Imamura, when all is said and done, was probably the greatest wacko director who ever lived.

I've only seen about half of his output (most regretfully missed thus far are Intentions of Murder, Profound Desire of the Gods, and A Man Vanishes -- the major works of his early period), but that won't stop me from offering a personal top 5 of Imamura's films:

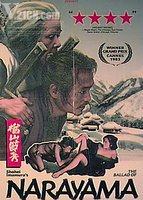

1. The Ballad of Narayama (1983)

2. Black Rain (1989)

3. The Eel (1997)

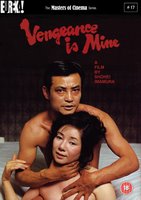

4. Vengeance is Mine (1979)

5. Dr. Akagi (1998)

For more, see Matt Prigge's write-up.