(Note: This post is reality-based, meaning you won't see me whining about how the Oscars fucked over Michael Haneke or Mathieu Amalric or Memories of Murder. Well, okay, maybe just a bit about Haneke.)

Snubbery.

1. King Kong -- Peter Jackson for Best Director/Naomi Watts for Best Actress/Best Picture.

Look, I understand. This little gnome went from being some obscure artgore nerd making flops starring Michael J. Fox to movie wunderkind, a gazillionaire with a shelf full of Oscars. And now, with his extreme makeover, the dude doesn't even look like a comic book shop clerk anymore. Hollywood's got nothing on him. So shutting King Kong out of the major categories might be just a mildly vindictive act of an industry stewing in schaudenfreude. Overstretching? How else to explain King Kong's snubs? Paying homage to classic Hollywood while showing off the latest and greatest in new Hollywood technology, King Kong is Hollywood escapism at its very best: you gasp, you gawk, you laugh, you cry, you sigh, you piss in your pants.

With King Kong and the hobbit trilogy, Jackson has taken a firm hold of the title of Best Big-Budget Filmmaker Working, wresting the crown from the long-dormant James Cameron and the uneven Steven Spielberg. No director can sweep the viewer into such richly detailed fantasy worlds quite like Peter Jackson. Few are as good at exposition and action-staging, and he's galaxies ahead of his peers in weaving CGI-creatures into live action. The key is that, unlike, say, Cameron or Lucas, he's a sensitive director of actors. Yeah, the big ape fights three T-Rexes in one of the most awesome fights ever. But how about those old New York scenes, with a fantasy Times Square that seemed to have emerged from dreams of Juilet Hulme (Kate Winslet in Heavenly Creatures, still Jackson's finest)? Jack Black doing a wicked Orson Welles parody? And how about making an ape-human love story that's convincing, and even moving? Much credit must be given to Naomi Watts, who's forced to make goo-goo eyes at a blue screen. Perhaps she lacked Fay Wray's vampiric sexuality, but this is a classic movie star performance, played opposite a giant computer generated ape, which is deserving of Oscar recognition if only for degree of difficulty.

2. Star Wars Episode III: Revenge of the Sith for Art Direction.

No need to dwell on the movie's big faults -- Lucas' clunky dialogue and (especially) Hayden Christensen, who played one of the medium's most fascinating, tragic characters as little more than an insipid brat. Let's marvel instead at the richly imaginative production design of the Prequels. Remember that planet where Obi-Wan, perched atop a giant alien lizard, hunts down General Greivous, with deep sinkholes and crevices that shoot straight into the planetary core? How about the magma covered rock that hosted the climactic fight? The sinewy trees that cover the Wookie planet? Or even Palpatine's living quarters, with its neo-futurist trappings?

It's true that Mr. Darcy's pad had some nice statutes, but come on. The Academy's production designers are historically biased towards masterpiece theater production design, but nominating Pride over Sith is plain absurd. A joke. An atrocity. An egregious mistake.

(I can't resist a plug for 2046, which features some of most jawdropping production design I've set eyes on. In a perfect world, William Chang would have five Oscars already.)

3. A History of Violence -- David Cronenberg, Best Director/Viggo Mortensen, Best Actor/Maria Bello, Best Supporting Actress.

Like a cinematic Edward Hopper, Cronenberg aims to demythologize the American dream by casting iconographic American motifs in a kind of clinical hyperrealism. I'd be leading the cheers if I didn't find the central idea -- that the American dream is built on the repression of a base ultraviolent instinct but must be defended by that letting loose that same instinct -- so unconvincing. The faults become especially glaring when you set it next to fellow Cannes competitor Caché, another art-thriller-cum-national-allegory about the return of the repressed that is entirely thought through.

However preposterous the story becomes, one can't deny Cronenberg's conceptual daring or rigor in execution, or blame Viggo Mortensen. Tom Stall's duality doesn't stem from schizophrenia but from an exercise of sheer will. Through Viggo's tricky, brilliant performance, we see how Tom's unruffled nobility and Joey's savagery can reside simultaneously in the same person.

As for Ms. Bello, did the voters not remember the animalistic sex scene on the staircase? The conversation with the sheriff and "Joey" in the living room? Bello's conflicted Edie was among the most impressive supporting performance I've seen all year. Predictably, the Academy goes with the gimmick turn by William Hurt.

4. Jeff Daniels (The Squid and the Whale) for Best Supporting Actor.

Yeah. He should be in supporting. I wish I had something to say about this excellent movie and the Daniels' fine performance. But I don't. Sorry.

5. Batman Begins for Best Screenplay/Best Editing.

It's not that easy to make a satisfying superhero movie. When it happens, as with Spider-Man 2, the industry should stand up and applaud. Think of the narrative economy of Batman Begins, a tale in which Batman's backstory, his inner demons, a love interest subplot, and a central story involving two villains are seamlessly woven together in a brisk 2 hours and change. Told with ruthless efficiency in a quick, but not frenetic pace, this new Batman origin story, the best Caped Crusader movie I've seen, shows off the director's considerable strengths (few can disseminate story and character information so clearly and efficiently -- no shot is wasted in a Nolan film) while minimizing his weaknesses (weak on atmosphere and mood, and poor usage of location). Nolan deserves his due.

D'oh! (Note: all of the Crash nominations probably belong here, if I could get myself to watch the blasted thing.)

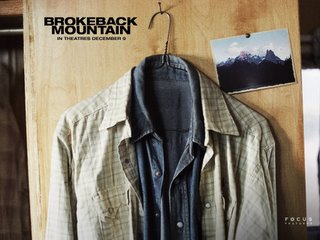

1. Jake Gyllenhaal (Brokeback Mountain) for Best Supporting Actor.

Never cared for the guy, but he surprised me with his sensitive perf as whiny bottom Jack Twist. I loved what Gyllenhaal did in that scene where he shaved very deliberately, his eyes moving just a tad, as he tries to resist ogling Ennis bathing behind him. Donnie Darko started to lose me when he grew that ridiculous painted-on moustache, but the real trouble here is putting Jack in supporting . This make a farce out of the whole lead/supporting distinction. Nearly half the movie is "about" Jack, and the first 3rd of Brokeback is told almost entirely from Jack's point-of-view. Look, you can't blame the studio's campaign strategy, since the supporting category is far less competitive than the male lead this year. They're just trying to get as many Oscar nods as possible. But it doesn't mean that the boneheaded voters should simply get herded around by gay cowboy PR people, following their directives like so much sheep.

2. The annual rant about lameass documentary and foreign film choices.

Dear fogeys, I have sat among you at Academy foreign film screenings, so I harbor no illusions that you can even sit through slow Taiwanese movies, much less vote to nominate one. But there's this movie called Caché that is playing right now, starring Daniel Auteuil (he's the other Frenchie with the big snout, the one from Bon Voyage, Apres Vous, and Manon of the Spring) and Juliette Binoche (you remember her from Chocolat). It is tense. It is dramatic. An elevator ride in which nothing happens can cause the viewer to break out into cold sweat. And it makes far more profound points about the colonial legacy and the causes of terrorism than the Oscar-feted Munich. I realize that this movie might've gotten more attention from you had Haneke cross-cut Binoche orgasming to memories of the October 1961 Algerian massacre in Paris. But notwithstanding the directorial error, this was still a good movie. Also, I thought after nominating both The Fog of War and Capturing the Friedmans two years ago, the documentary committee was finally starting to get it. My mistake.

3. Keira Knightley (Pride & Prejudice) for Best Actress.

Thanks, Academy. Now I'll be forced to hear the trailer voice-over guy intone "Academy Award nominee Keira Knightley" every year for the rest of my life. Sure, if an award were given for the most charming sun-dappled smile, Keira would be a top contender. Alas, this is an award for performance in a lead role. While the not-very-talented Ms. Knightley acquitted herself better than I expected in this superior adaptation of Jane Austen's old chestnut, she, like Winona Ryder, can never quite shake her contemporary mannerisms. Occasionally she comes off distactingly like someone who's itching to text message her buddy shopping at Forever 21. To be fair, most of the time she's serviceable. But when was "serviceable" award-worthy?

4. William Hurt (A History of Violence) for Best Supporting Actor.

No. This movie might've been the masterpiece everyone else thinks it is without the last twenty minutes, of which our yuppie-bad-boy-playing-gangsta was the most prominent distraction.

5. Munich, for Best Picture, Director and Screenplay.

It's hard not to feel a twinge of sympathy for Spielberg and Kushner, assaulted by Zionist zealots on one end and anti-Zionist zealots on the other. Zealots suck. Worse still is the attack from Leon Wieseltier, whose erudition I hold in high esteem. He argues that Munich promotes a "false equivalence" -- except it doesn't. Something can show the costs of aggressive counter-terrorism tactics without condemning the necessity of such tactics, which is what Munich does (though Wieseltier is correct in identifying Spielberg's craven technique of trying to provoke without risking offense). The real problem is Spielberg's heavy-hand, baring down on strong material and turning grim political thrillers, light-hearted romps, and cerebral sci-fi alike into mush. Spielberg, I've come to believe, is our generation's John Ford, another major artist afflicted with an incurable case of the schmaltz. Like Ford, perfection will continue to elude Spielberg's even most accomplished works as long he insists on layering a slice of American cheese over everything he serves up.

Good job, self-congratulatory middlebrow industry bootlickers.

1. Brokeback Mountain. How refreshing that the best American movie of the year will be recognized as such; it's only too bad that Heath Ledger, who towers over the acting field this year, won't share in the glory.

2. Emmanuel Lubezski (The New World) for Best Cinematography. Okay, I'm making plans to catch the shorter cut of this again, just to make sure it's not me but the geeks over on this blog and elsewhere that are insane. But even if Malick's cineaste cause celebre isn't the greatest movie since 2001: A Space Odyssey, it's pretty hard to dispute the claim that this is one of the most ravishingly beautiful films in recent memory, deserving of an all-time Oscar in this category. (Note: 2005 saw a bumper crop of films that, whatever their other flaws, are among the medium's finest ever displays of lighting and composition captured on celluloid. I'm thinking of 2046, The New World, and Three Times. And I bet Claire Denis and Agnes Godard's L'intrus belongs here, too, but I'll have to wait until March to confirm this.)

3. Noah Baumbach (The Squid and the Whale) for Best Original Screenplay.

Sculpting one's childhood trauma into shape is tough enough. To turn your parents' divorce into such a tough, tender, and funny story -- and not letting the squabbling, narcissistic parents off the hook without hanging them -- that's award-worthy. Alright, that wasn't much. But I tried, okay?

4. Catherine Keener (Capote) and Rachel Weisz (The Constant Gardener), for Best Supporting Actress.

They are both great, I imagine. Keener is the most watchable American actress today and was terrific playing against type in The 40-Year-Old Virgin. I've faith that she's doing her usual excellent job in Capote as Harper Lee. And Rachel Weisz. Yum. Though I have some of her finest moments stored in my hard-drive, I can only guess at her flexing her awesome powers in the role an ill-fated do-gooder. Perhaps this weekend I'll find out...

5. George Clooney trifecta; and David Strathairn (Good Night, and Good Luck.) for Best Actor.

If you can be anyone else on earth, who would you choose to be? To me, it's a no-brainer -- the Sultan of Brunei, of course. But if the Sultan were already taken, I might well choose George Clooney, the coolest man around, and perhaps the only movie star in Hollywood worthy of admiration.

For a guy who has it all, he appears grounded, finds time to smack down Bill O'Reilly, and seems to actually care about the quality of the projects he's involved in. Or maybe he just has a great publicist. Still, in fifty years time, I imagine Clooney's films will still be seen while Brad Pitt and Mel Gibson's titles languish in some mega-server in Kenya. Hollywood's finally given him offical props, and it looks like he'll be taking home a statuette for putting on some pounds. Cool -- though I'd give him a retroactive Oscar to him for Out of Sight instead. But I'm rooting for him here just so I can see an entertaining speech. Excellent helming job, too.

For a guy who has it all, he appears grounded, finds time to smack down Bill O'Reilly, and seems to actually care about the quality of the projects he's involved in. Or maybe he just has a great publicist. Still, in fifty years time, I imagine Clooney's films will still be seen while Brad Pitt and Mel Gibson's titles languish in some mega-server in Kenya. Hollywood's finally given him offical props, and it looks like he'll be taking home a statuette for putting on some pounds. Cool -- though I'd give him a retroactive Oscar to him for Out of Sight instead. But I'm rooting for him here just so I can see an entertaining speech. Excellent helming job, too.I love those up-angle shots of the neatly dressed Edward R. Murrow, legs crossed in his chair right before going on air, in deep contemplation as a cigarrette dangles from his bony fingers. Clooney's film is about journalistic courage, but what it captures most perceptively is the dynamic of work, how well-meaning, competent people may squabble on the job, but they'll get it done when it counts.